THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINENew York, New York

4 manuals, 151 ranks

year complete, 2008

Early on the morning of December 18, 2001 a massive five-alarm fire at the Episcopal Cathedral of Saint John the Divine lit up the skyline of Morningside Heights in Manhattan. The fire completely destroyed the Cathedral’s gift shop, housed for many years in the unfinished North Transept, but fortunately failed to take a firm hold in the Crossing, Nave or eastern regions of the Cathedral itself. It did, however, cause considerable physical damage to two seventeenth-century Barberini tapestries and there was also extensive smoke and soot damage throughout the building and its contents. These conditions particularly affected the landmark Æolian-Skinner pipe organ. Ultimately, the process of cleaning the building necessitated the removal of the instrument.

History

The signing of the original contract for a four-manual organ in the Cathedral to be located behind facades at either side of the Great Choir took place in 1906. After slow progress in the building’s construction, the Ernest M. Skinner Organ Company of Boston, Massachusetts completed installation of the instrument in 1910 as the firm’s opus 150. At the time, it was a landmark organ and contained a number of innovations such as Skinner’s first 32’ Violone, an improved design of Tuba Mirabilis and Skinner’s first Gamba Celeste stop of flared pipes in the Solo division. A Skinner organ was, in Leslie Olsen’s phrase, “The Stradivarius of its day” and, under the capable management of Dr. Miles Farrow (1871-1953), the Cathedral’s first Organist and Choirmaster, the Cathedral’s Great Organ soon earned for itself the reputation of being one of the finest organs in North America.

The original architects of the Cathedral, Messrs. Heins & LaFarge, had planned the building in the Byzantine-Romanesque style, but after the completion of the Choir and enclosure of the rough structure of the Crossing with a temporary Guastavino dome and three walls in 1910, a change in architectural style was sought by the Bishop and Board of Trustees. Ralph Adams Cram took over as architect in 1916, and the concept was changed from Romanesque to a modified Gothic architectural style. Cram’s plans for the world’s largest Gothic cathedral have yet to be fully completed. However, his magnificent Nave, Baptistry and remodeled Choir, and his concept of having several chapels designed by different architects according to the nationality represented by the particular chapel produced an intriguing mixture of architectural styles – giving the building the feel of some medieval European cathedrals that grew slowly over many years and centuries.

By the late 1930s, completion of the Nave was achieved and Cram’s planning had reached a sufficiently advanced stage that remodeling of the original Choir vaulting was to be undertaken to bring the architecture of the Great Choir more in harmony with that of the newly completed Nave. In 1938, E. M. Skinner & Son of Methuen, Massachusetts was engaged to move a portion of the organ to the Nave, where services were to be held for three years while reconstruction of the Great Choir was underway. The Solo and Choir divisions of the organ remained in the chambers, sealed in their Keene’s Cement expression enclosures, but the console, Great, Swell, the Solo Tuba and a large portion of the Pedal were reinstalled near the east end of the new Nave, which was separated from the Crossing and Choir by a massive temporary construction wall. In the summer of 1941, the console was taken to Skinner’s factory in Methuen for releathering and the addition of 4 more general pistons, bringing its total to six. During this period, a temporary Everett Orgatron rented from John Wanamaker, New York served as the Cathedral’s musical instrument. Reinstallation of the relocated divisions of the pipe organ in the newly modified Great Choir chambers also took place during this period, and the temporary wall was finally demolished, revealing for the first time the new vista of the Cathedral’s Nave, Crossing and Great Choir. The festival service celebrating the completion of the Nave and Choir remodeling was held on November 30, 1941, a week before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that took the United States into World War II. Ralph Adams Cram and Ernest M. Skinner were both in the procession.

By the end of the War the tonal design of the Skinner organ had become somewhat dated with the development of the “American Classic” style of instrument that was then becoming fashionable. Perhaps more importantly, the Cathedral’s interior had grown dramatically in size from its state when the original organ was installed. After its reinstallation in 1941, the 1910 organ was found to be at a disadvantage in the greatly expanded Cathedral’s new acoustic. In 1950, therefore, the Æolian-Skinner Organ Company of Boston, Massachusetts, under the direction of G. Donald Harrison, was commissioned to examine the organ and make recommendations for its rebuilding. A new specification was proposed on January 10th of that year, but it was not until December 7th of 1951 that a contract was finally signed. Interestingly, the contract included a clause stating that “In view of the nature of the contract involving the rebuilding of an old instrument, it is therefore stipulated that it is impractical beforehand to decide exactly what the ideal specifications of the work should be for the greatest result. Therefore the Builder reserves the right to modify the enclosed specifications as he sees fit, with the advice of Dr. (Norman) Coke-Jephcott as the work progresses”. In a brochure about the rebuilt organ produced in 1954 by Æolian-Skinner, Harrison noted that the tonal fabric grew from a “tentative” specification as a result of much study of the effect of the organ at services, and through work with many experimental pipes in the Cathedral. It was realized that “ a very special scaling would be necessary”, and the contract specification was dramatically revised.

The work began almost immediately. This project, titled as Æolian-Skinner’s opus 150A, was carried out under conditions of great difficulty. Æolian-Skinner was nearly overwhelmed with work as the end of the war and depression years preceding it brought a flood of major contracts. Harrison and his associate Joseph Whiteford were pushed by Æolian-Skinner’s obligations of building multiple large contracts almost simultaneously. For the Cathedral project, money was relatively tight and the budget was therefore limited. Furthermore, the tonal changes and expansion that were made to the organ had to be carried out without dismantling an instrument that was in regular use. This also meant that in some cases new windchests to accommodate the additional stops had to be placed in less than ideal positions.

Nevertheless, G. Donald Harrison and the staff of Æolian-Skinner were able to create a magnificent instrument that has rightly taken its place as one of the world’s most famous organs, and one of Æolian-Skinner’s most important achievements. The skillful melding of older pipework from the original Skinner organ of 1910, and new material introduced into the organ from 1951 to 1953 produced a new instrument of remarkable clarity, suavity and “emotional grip”, to borrow a phrase of Harrison’s.

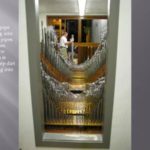

To cap the rebuilding project, Æolian-Skinner created what became perhaps their most famous single stop and the crowning tonal voice of the instrument, the State Trumpet. Voiced on fifty-inch wind pressure, with its gleaming aluminum leafed pipes projecting from the gallery beneath the Great Rose Window, it is located high at the west end of the Cathedral nearly 500 feet from the main divisions of the organ. It was first used in Easter Day services on April 5, 1953. G. Donald Harrison and Joseph Whiteford were in attendance.

1991 to 2000

Beginning in 1991, a program of restoration in the Great Organ was undertaken, under the leadership of then Cathedral Organist Dorothy J. Papadakos, with work performed by the Cathedral’s Organ Restoration Shop – Douglass Hunt, Curator of Organs. The innovative Adopt-a-Pipe program attracted contributions from hundreds of people and foundations, and allowed the accomplishment of significant work in the organ through the turn of the century. Work was done in stages, as fund raising allowed, once again with the organ in regular use for the Cathedral’s many services and events. Restoration of the State Trumpet was the first project undertaken, followed by work in the Choir, Swell, Bombarde and Solo divisions. However, the fire on December 18, 2001, and resulting smoke and soot damage throughout the Cathedral changed the magnitude of the undertaking, and shortly after the fire, Mr. Hunt recommended a new approach.

2009 –

Following the fire a thorough cleaning and restoration of the whole building’s interior and furnishings was undertaken at a cost of $41,000,000, under the direction of Stephen Facey, Executive Vice President of the Cathedral. The work has included cleaning of all the stonework, woodwork and the numerous art works found throughout the building. As a part of this project, Quimby Pipe Organs, Inc., of Warrensburg, Missouri was selected by the Cathedral for post-fire cleaning and restoration of the Great Organ, with Mr. Hunt acting as Project Consultant.

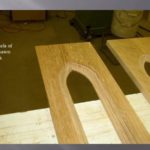

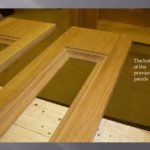

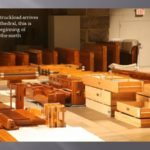

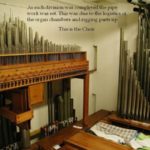

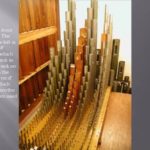

Apart from the oak façade casework and three expression enclosures, the entire organ was removed from the Cathedral, packed and loaded into five 18-wheeled trucks and transported to Missouri for restoration. In consultation with the Project Consultant, Michael Quimby drew up detailed guidelines for comprehensive restoration of the windchests and pipework. The work in the Quimby shops took over two years and to date is one of the largest projects undertaken by Michael Quimby’s firm. All mechanical components received thoroughgoing cleaning, repair and releathering, including the near 100 year-old Skinner chests still functioning in the organ. (It may be safe to say that the restored Skinner wood-cap electro-magnets are now some of the oldest functioning electrical devices in Manhattan.) All pipework has been meticulously cleaned; metal pipes have had their dents removed and wood pipes were repaired and stoppers repacked. With strict prohibitions against alterations to the original voicing and balances between ranks, each stop was carefully assessed and only corrective remedial voicing was undertaken to bring errant pipes back into regulation with their neighbors. While non-speaking, the restoration of the numerous zinc façade pipes displayed in the six oak cases proved to be a far more extensive job than expected.

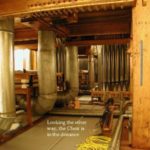

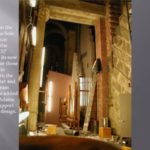

Although it was desired to make as few changes to the organ as possible, a priority during the work has been to correct certain difficulties with the arrangement of the instrument in the chambers. A problem with the original Skinner layout of the chambers was that the large pedal pipes were placed for their own greatest advantage, which put some of the other pipework at a loss, particularly after expansion of the building in the 1930s necessitated the sound of the organ to reach far greater distances. As rebuilt and enlarged in 1953, the Great division had to be spread through 2/3rds of the length of the South chamber, working around 16’ and 32’ wood Pedal pipes that remained in place during the rebuilding project. Thus, for example, the windchests supporting eighteen ranks of new upperwork incorporated into the expanded Great division had to be placed on a level above that of the original Great windchests, and at some distance from them. This meant that the major Great mixtures were often at a different temperature from the remainder of the Great pipework, and thus rarely in tune with the rest of the principal chorus. With a variety of chest actions and winding, and a sprawling layout, the Great division suffered from a lack of speech precision.

By a deft rearrangement of the Great and Pedal chests in the South chamber planned by Eric Johnson, the Great is now entirely together behind the large South façade. The 32’ octave of the Open Bass and the 32’ Violone have traded chamber locations, aiding in the rationalization of the Great, and placing the enormous Open Bass pipes with the remainder of its rank in the North Chamber. The Swell, Choir, Solo, Bombarde and North Pedal remain in the locations as designed by Skinner and Æolian-Skinner.

The Æolian-Skinner Bombarde division windchest was designed for non-hooded reed pipes, but hooded pipes were ultimately used as the 1950’s rebuilding project evolved. Without primary actions for the 16’ rank, the chest did not function entirely well and space for the 8’ Trompette Harmonique and Tierce Mixture was seriously compromised because of the hooded reed resonators. This chest has now been rebuilt with new channeling and primaries, and there is now adequate room for all pipework.

A few minor tonal changes have been made. The most important of these is the addition of a 16 ft. Subbass to the Pedal division, using a vintage Skinner chest and pipes. Another change to the Pedal division has been to separate the 5-1/3 ft. rank from the rest of the Pedal Mixture. On its own stop action since 1953, this change required nothing other than a separate stop knob, but gives a bit more registrational flexibility. (Interestingly, a separate 5-1/3’ Quinte had been a part of the contract’s Pedal stoplist.) The original Skinner 32 ft. Bombarde, whose pipes stood silently in the chamber after the 1950s work, has been revoiced and reinstated, (and renamed Contre Ophicleide to distinguish it from Æolian-Skinner’s Contre Bombarde). The Cello III, a Pedal stop unique in Skinner’s work and whose pipes had been stored in the organ, has been reinstated on its original actions. The 8’ Spitzflöte, which replaced the Cello in 1963, has been retained on another vintage Æolian-Skinner chest.

A 3-1/5 ft. Grosse Tierce, again using vintage Skinner pipework, has been added to the Great on actions left vacant in the 1953 rebuilding. A new 8 ft. Flauto Dolce built to Æolian-Skinner patterns has been inserted in the Swell, replacing another rank that did not function well with the céleste rank installed by Æolian-Skinner in 1953. In the Solo, the French Horn, a stop added by Skinner at some point after the original 1910 work, and which replaced an original mixture stop called “Cymbale”, has been placed on a vintage Skinner chest originally constructed for a French Horn, with the necessary larger valve sizes required by such pipework. An 8 ft. Corno di Bassetto now stands on the old Cymbale actions, and an 8 ft. Diapason has been inserted on the original Stentorphone actions left empty in 1953, both stops again using vintage material.

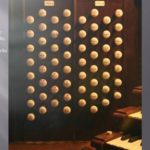

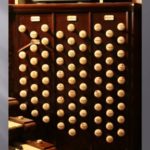

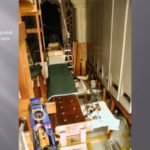

The original Skinner console had been modified in the 1953 rebuilding, and its oak shell damaged over many years. In addition, the deep shell of the console, necessary to house Skinner’s original massive mechanism, was largely empty after Æolian-Skinner installed new console components, with remote combination machines. After discussions between Michael Quimby, Eric Johnson and Douglass Hunt, the decision was made for the Quimby firm to build a new console in accordance with Æolian-Skinner dimensions and styling, and reproducing much of the elegant carved detail from the original shell, but in a more compact size to better fit the available space in the console loft. The new console, of quarter-sawn white oak and French-polished mahogany, is fitted with manual keys and other components made by Harris Precision Products, and electronic components by Solid State Organ Systems. The console has also been turned from its previous position, moving the organist out from under an arch, and placing the player more in the acoustical environment of the Great Choir where the organ and choir are heard to better advantage.

Acoustical Work

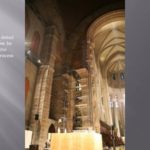

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is a traditional masonry structure, largely constructed of limestone and granite. Much of its vaulted interior, including the remarkable Crossing dome is the work of the Guastavino firm of New York City. Rafael Guastavino’s adaptation of traditional Catalan terracotta tile construction by the use of Portland Cement led to a system of vaulted construction that was both stronger and lighter than that built with conventional stonework. In addition, in the time before electronic voice amplification was well developed, Guastavino, working in collaboration with Ralph Adams Cram and the acoustician Wallace Sabine, developed a ceramic acoustical tile that could be made to mimic the appearance of limestone, but which was designed to attenuate reverberation, considered an unfortunate byproduct in large worship spaces constructed with traditional materials. This new tile, called Akoustolith, was used in the construction of many masonry church buildings of the time, with the effect of deadening the natural lively reverberation, so important to corporate worship, hymn singing, the traditional Anglican choral repertoire and the organ. At the Cathedral, however, the sheer size of the space, and the vast cubic footage contained by it guaranteed a long reverberation. The Akoustolith facing the high vaulting merely served to obscure clarity of diction in choral music, the organ and other musical instruments.

With the opportunity afforded by scaffolding to reach the high vaults for the first time in decades, the Project Consultant recommended that the vaulting be sealed to improve the projection of the choir and organ from the Great Choir outward to the Crossing and Nave. In consultation with the noted acoustician Dana Kirkegaard, it was determined that at least the high vaulting east of the Crossing, and the first double bay west of the Crossing should be treated. With a limited budget, this was all that was possible, but with the masonry freshly cleaned and repaired, and difficult access to the vaulting made possible by the complex scaffolding already in place for cleaning, it was agreed to proceed with sealing work in these areas. Although the building already had a lengthy period of reverberation, as a result of the treatment of the Akoustolith surfaces the character of sound in the Cathedral is now much clearer, and this has had a very beneficial effect on the sound of the organ and music in general.

The blowing plants for the organ have been completely revised, offering the organ a much cleaner air supply, and greatly reducing the background noise in the Cathedral from the operating blowers. As redesigned by Dana Kirkegaard and Douglass Hunt, the main blower rooms are now acoustically isolated from the Cathedral, and include new intake noise attenuation and air filtration equipment. The Spencer Orgoblos have been faithfully restored and provided with new static reservoirs by Quimby Pipe Organs.

Associates of Quimby Pipe Organs, Inc., who made significant contributions to the restoration of the organ in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine include David Beck, Steve Blackstock, Andrew Burkhart, Mark Cline, Bart Colliver, Tim Duchon, Chris Emerson, Timothy Fink, Charles Ford, Isabelle Hendriksen, Eric Johnson, Joe Lambarena, Kevin Lors, Wes Martin, Brad McGuffey, Mark Muller, Joseph Nielsen, Erik Otter, Gary Phillips, Michael Quimby, Janille Rehkop, Jim Schmidt, Mike Shields, John Speller, Chirt Touch, Nah Touch, and Elizabeth Viscusi. John Bishop, Executive Director, and Amory Atkin, President, and associates of The Organ Clearing House participated in the removal, and reinstallation. The Cathedral Curator of Organs, Douglass Hunt, served as Project Consultant on behalf of the Cathedral, overseeing the work and acting in several additional roles in both the actual restoration of the organ, and the building itself.

The rededication of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine took place at a special service on the morning of Sunday, November 30, 2008 – the 67th anniversary of the original dedication of the full length of the Cathedral. Participants included the Dean of the Cathedral, the Very Rev. James Kowalski; the Bishop of New York, the Right Rev. Mark Sisk; Stephen Facey, Executive Vice President of the Cathedral; the Cathedral’s new Director of Cathedral Music and Organist, Bruce Neswick; its Associate Organist and Choirmaster, Timothy J. Brumfield; the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, the Most Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori; and both the Senators for New York, the Honorable Hillary Rodham Clinton (now Secretary of State in President Barack Obama’s cabinet) and the Honorable Charles Schumer. At Evensong later that day, the Great Organ was rededicated before a capacity congregation.

The organ has 151 ranks of pipes, 101 actual stops (not including borrows, duplexes, tremulants or percussions) and 8,514 pipes on 7 divisions spread over 4 manuals and pedals. Manual and Pedal Nave divisions, discussed as a part of the 1950s project but never installed, have also been prepared for in the new console.

Read or download the cover feature article from TAO (includes tonal spec)